A Q&A discussion with David Lundgren, CMT CFA, about the MOTR philosophy of investing

Q: Why should an investor consider active management when they can just passively invest in the index at such a low cost?

Q: Why should an investor consider active management when they can just passively invest in the index at such a low cost?

A: Well, if I pitched a strategy that had regular drawdowns of 20-50%, and in really bad cases, more than 80%, and when those drawdowns happen, it might take more than a decade to recover your investment, all in exchange for 9% returns”, most investors would say, “No thanks, I’ll stick with passive ETFs.”

But I just described passive Investing! People lose sight of the fact that passive index investing is just another investment strategy, but one that offers no plan for either navigating serious market drawdowns or managing individual stock selection risk.

Q: So, you’re saying that investors either underappreciate or blindly accept the risks that are inherent in passively investing in the index? What are the risks more specifically?

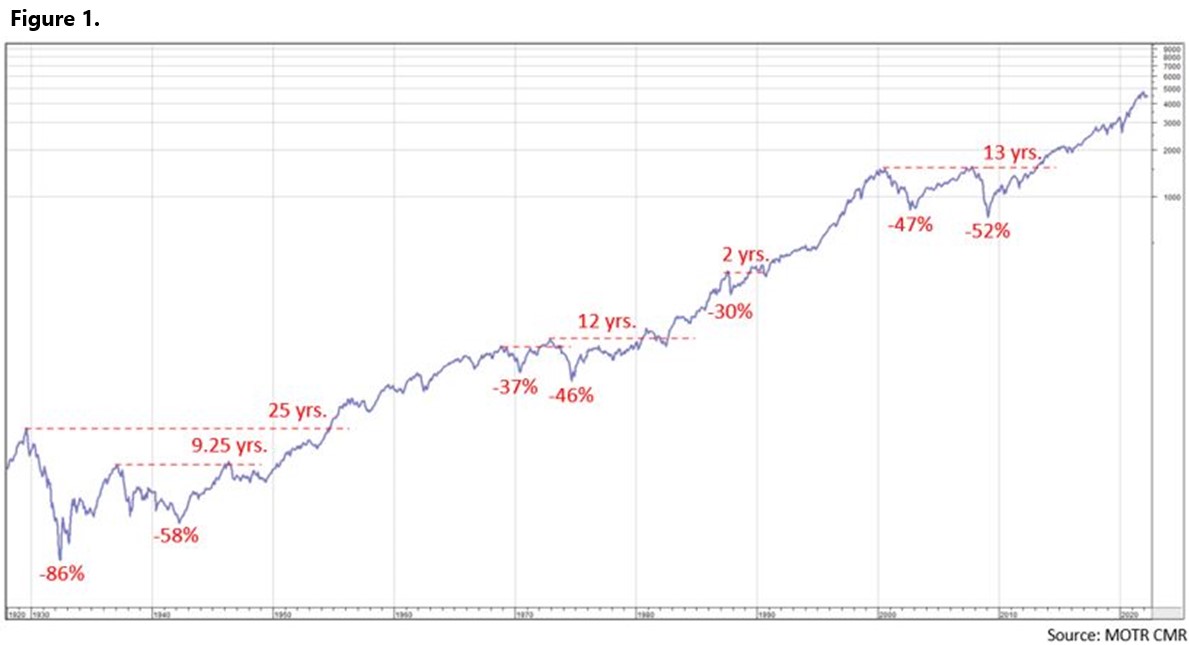

A: Well, first there is drawdown risk. Since 1927, the market has undergone several major declines ranging from -30% to -86%, and when these declines have happened, it has taken anywhere from 2 years to more than two decades to get your money back. Passive, buy and hold investors have no choice but to sit through these massive declines. (Figure 1).

Q: How would an active, tactical manager navigate declines like these?

A: In a big picture sense, the market can only do one of three things: go up, go down, or go sideways. I believe that at any given moment, you can identify sufficient evidence to eliminate one of those three scenarios. Since you can never really eliminate “sideways” (the market can literally just stall out for any number of reasons), what we’re really trying to do is eliminate “Up” or “Down”, leaving us to invest for either “Sideways to Up” or “Sideways to Down”.

To do this, I utilize a systematic research process that I have developed over the more than three decades that I have been in this business, and that process guides my research recommendations in the MOTR Weekly Report and the Monthly MOTR Checkup video series, as well as my positioning in a private long/short fund that I manage.

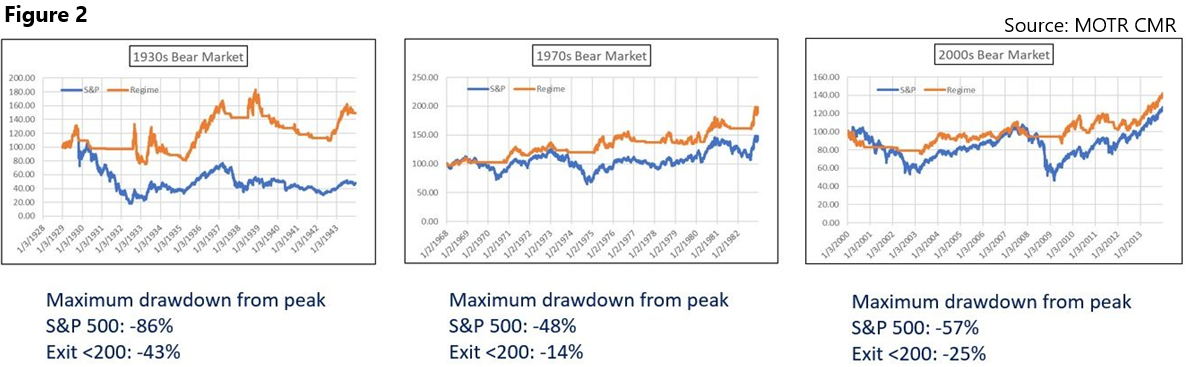

The process is primarily based on three inputs: price momentum, absolute price trend, and relative price trend, all measured over multiple timeframes across more than 3,000 stocks and ETFs. When our Risk Gauge model has identified a “Risk Off” condition, we feel we have identified enough evidence to eliminate “Up” from consideration, leaving us to position for “Sideways to Down”. In such instances, one simple defensive strategy might be to go to cash when the market closes below its 200 day average and stay in cash until the market closes back above its 200 day. I am certainly not advocating for this highly simplistic approach per se, but we can see how a simple strategy such as this might have helped sidestep the major bear markets of the past 100 years. (Figure 2).

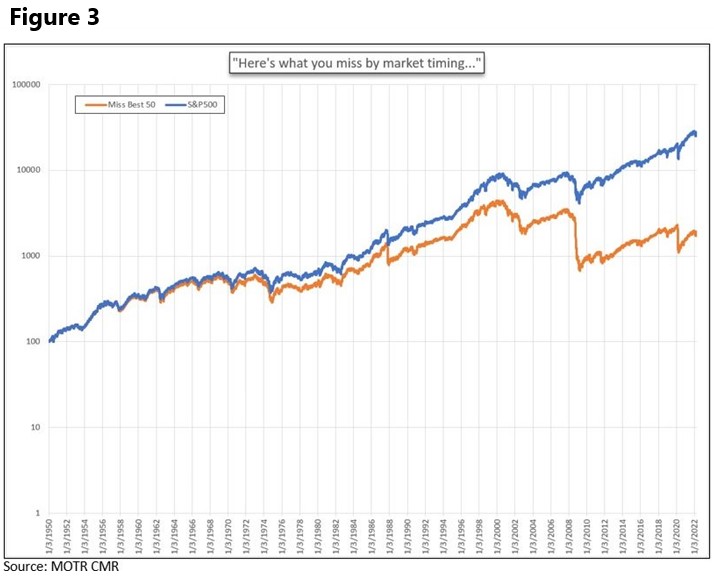

Q: That makes sense, but how would you respond to those who say that trying to “time” the market is a bad idea? They often site studies that show what happens to your long-term performance if you inadvertently miss the market’s 50 best days as a consequence of trying to avoid bear markets. (Figure 3).

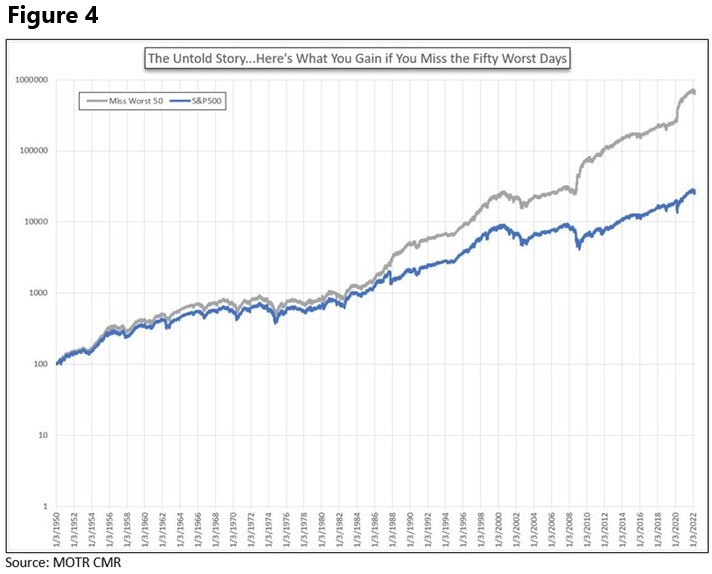

A: Yes, I am aware of those studies, and I am also aware of the tactical investor community’s counter punch, which is to show a chart that demonstrates how much your long-term returns improve when instead, you avoid the market’s 50 worst days as a result of trying to sidestep bear markets. (Figure 4).

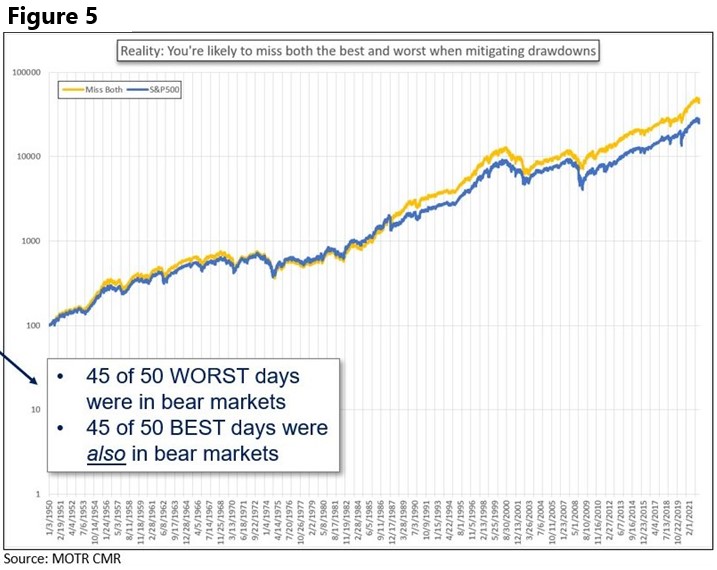

Unfortunately, neither party is telling the whole truth. The fact is that by raising cash during “Risk Off” bear markets, using something as simple as closing below the 200 day average as described earlier, an investor actually avoids both the majority of the market’s worst days and the majority of the market’s best days! Because bear markets are so volatile, we find that both 45 of the 50 worst days, and 45 of the 50 best days, were actually recorded while the market was below its 200 day average. So, by investing defensively during bear markets, investors actually sidestep most of that destructive volatility. (Figure 5).

Q: You mentioned there was another major risk that passive investors face. Can you explain?

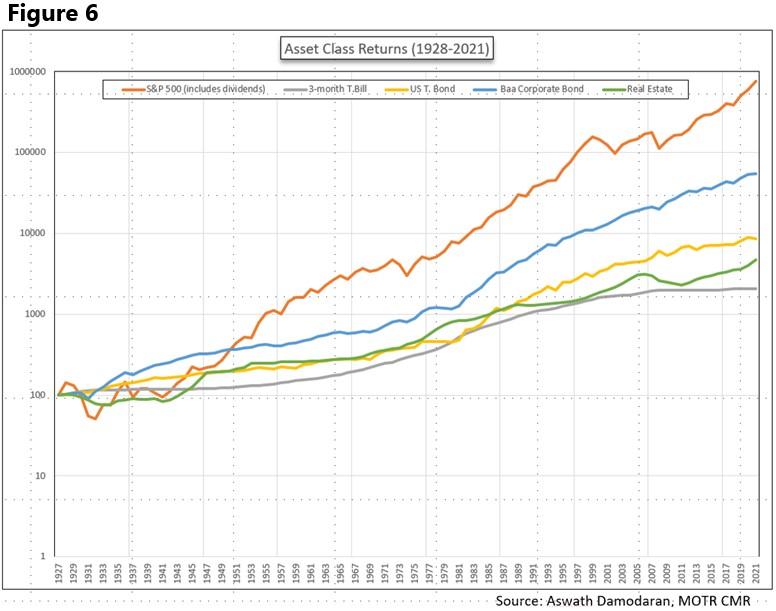

A: On the one hand, the benefits of equity ownership are indisputable relative to other asset classes. According to data provided by Professor Damodaran, the S&P has created more wealth by a long shot when compared to treasury bills, treasury bonds, corporate bonds, and real estate. (Figure 6).

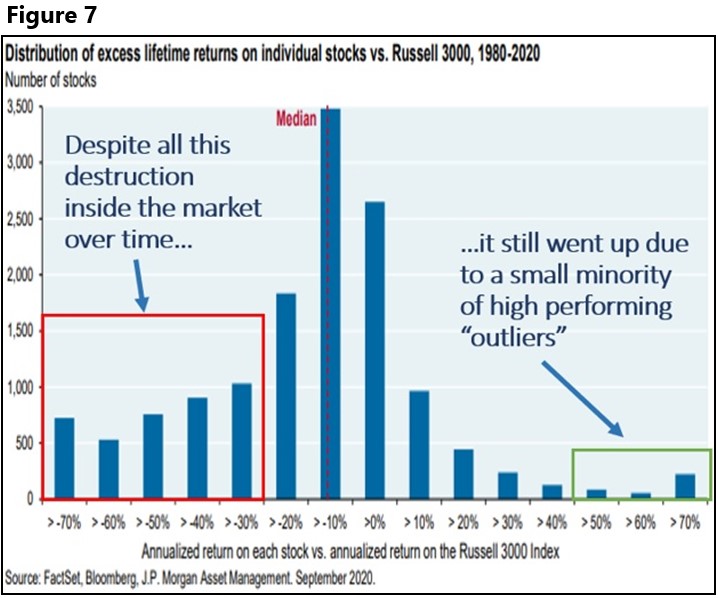

This performance spread likely contributes to the blind acceptance of the drawdown risks discussed earlier, but another significant risk exists that is actually hidden from plain sight. According to a recent J.P. Morgan report, almost half (42%) of the stocks that are eventually removed from the Russell 3000 index exit at a lower price than where they were when they were first added. Further, a full 66% of stocks in the index wind up underperforming while they are in the index. (Figure 7)

So, beneath the surface of the index, there is an awful lot of capital destruction going on, and again, passive investors have no choice but to own these money losing stocks.

Q: Wow, that is really surprising! How is it that the market tends to go up over time then, despite being dragged down by all of these money losing stocks?

Q: Wow, that is really surprising! How is it that the market tends to go up over time then, despite being dragged down by all of these money losing stocks?

A: This gets to the difference in skew that exists between winners and losers. Stocks can only go down 100% (they can’t go below $0.00), but winners can, and do, go up hundreds, if not thousands of percent. According to J.P. Morgan’s study, a very small percent of stocks (10%) in the Russell 3000 have contributed most of that index’s gains over time. (Figure 7) These are history’s biggest winners that, with perfect hindsight, we all know and love.

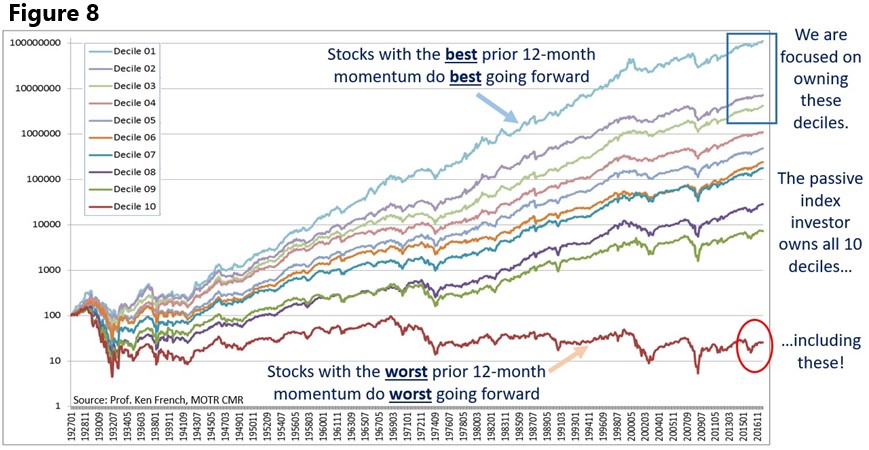

In other words, the dirty little secret is that passive investing is really just a momentum strategy, in the sense that the stocks that do best are allowed to get bigger and bigger. However, in passive index investing, there is no risk management strategy for dealing with the losers. They are allowed to keep dragging down the benchmark until they are eventually removed from the index. In momentum investing, we attempt to own those same winners as well, but we actively try to avoid the losers. (Figure 8).

Q: What is momentum investing?

A: Momentum investing is based on the idea that stocks that have done well recently tend to continue to perform well in the future, and vice versa. There have been many academic studies conducted on data going back hundreds of years demonstrating that stocks in the top deciles of momentum tend to outperform stocks in the bottom deciles of momentum. (Figure 8)

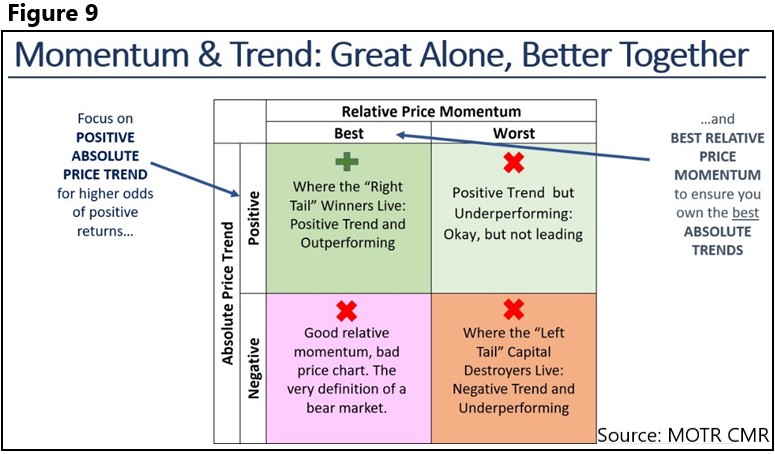

Q: In one of your earlier comments, you mentioned that you use three inputs, one of which is momentum. Given the evidence in support of buying the top deciles of momentum, why not use only momentum? Why use absolute and relative price trends?

Q: In one of your earlier comments, you mentioned that you use three inputs, one of which is momentum. Given the evidence in support of buying the top deciles of momentum, why not use only momentum? Why use absolute and relative price trends?

A: Momentum has its clear benefits, but as with all things in life, it has its drawbacks too. Ranging from having very high turnover at times, to the infamous “momentum crash”, there are good reasons for not relying exclusively on momentum for stock selection purposes.

For me though, the biggest reason is that momentum is price trend agnostic, meaning that a momentum investor will always own the top decile of momentum, even if the stocks in the top decile got there by simply going down less than everything else, which is very common in bear markets.

In this case, you could have stocks that have fallen -35%, for instance, but because everything else has fallen say -50% or more, they still make it into the top decile. In this sense, there is no risk management for momentum investors during bear markets.

Q: What about absolute price trend? Is that the same thing as “trend following”?

A: Precisely, and like momentum, trend following has many positive attributes, including its focus on only owning stocks that are in positive trends, and avoiding those that are in negative trends. As with momentum, however, there are drawbacks. In very strong bull markets, when virtually every stock is in an uptrend, it becomes very difficult to know which stock to own. Trend following makes no distinction between one positive trend and another.

What I have found is that by combining momentum analysis with trend following, we are able to accentuate the strengths of each strategy, while guarding against each of their weaknesses. In other words, in bull markets, momentum will enable us to find the best performing positive trends, while trend following won’t permit us to own negative trends in bear markets, even if they are in the top decile of momentum. (Figure 9).

Q: Momentum seems pretty clear. The best performing stocks are in the top decile, while the worst performing stocks are in the bottom decile. As an investor, you want to focus on owning top decile stocks while avoiding the bottom decile. (Figure 8) What about trend following? How does that help you find potential opportunity on the one hand, and protect you from risk of loss of capital on the other?

A: Trend following is a very simple, yet incredibly powerful concept. In essence, a stock can go from $20 to $100 for any number of fundamental reasons, and more often than not, fundamental investors argue amongst themselves about the validity and accuracy of those fundamental drivers all the way up (i.e., Tesla).

However, in trend following, it can be said unequivocally that a stock absolutely cannot go from $20 to $100 without first getting above $25, and once it does get above $25, nobody can argue that it hasn’t. We can certainly argue fundamental reasons for why it shouldn’t have gotten above $25, but we can’t sanely argue that it hasn’t gotten above $25. In other words, while the rules of fundamental investing are personal, the rules of trend following are inviolable. We must all abide by them, whether we know it or not, and certainly whether we like it or not.

Q: How do you incorporate trend following into your process then?

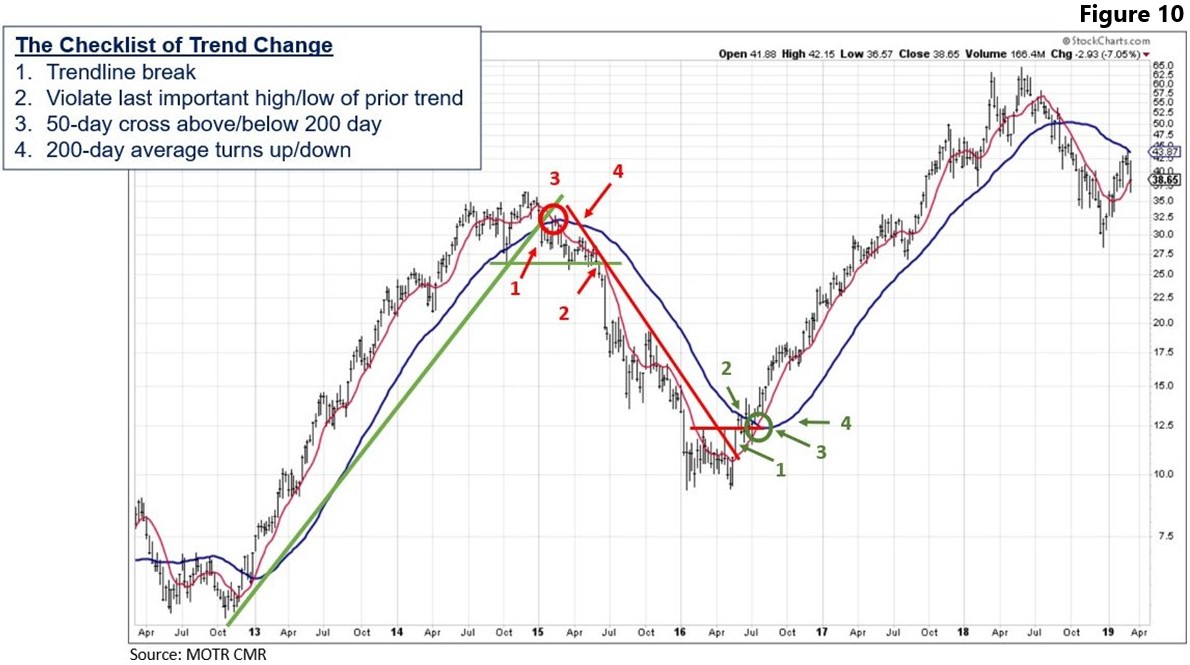

A: To help make this concept more practical, when I was teaching Technical Analysis at Brandeis University’s International School of Business, I taught a concept I called The Check List of Trend Change. (Figure 10) Once a positive price trend is underway, four things have to happen first before any meaningful risk is present.

A: To help make this concept more practical, when I was teaching Technical Analysis at Brandeis University’s International School of Business, I taught a concept I called The Check List of Trend Change. (Figure 10) Once a positive price trend is underway, four things have to happen first before any meaningful risk is present.

- First, the uptrend support line has to be broken. Stated again, a stock in an uptrend cannot embark on a downtrend without breaking this trend support first. It is literally impossible.

- Second, the stock has to break below the last swing low of the prior uptrend. By definition, according to Charles Dow, once the prior low is broken, you technically now have a lower low, and therefore you have a downtrend.

Therefore, the first two boxes in the check list are referred to as coincident indications of trend change, while the remaining two boxes on the check list are referred to as lagging indications of trend change, since they generally happen after the trend has already changed.

They are…

- Third, the short-term moving average must close below the long-term moving average, and

- Fourth, the long-term moving average must turn down.

In my process, during “Risk On” regimes, as identified by our Risk Gauge, I am exclusively focused on investing in high momentum stocks where I have been able to check these four boxes in favor of positive price trend. Of course, in “Risk Off” environments, I will also short stocks with poor momentum where I can also check the four boxes in favor of a bearish, or negative, trend.

Q: You mentioned how fundamental trends are what drive stocks higher over time. Granted, as you say, the actual drivers might be different from cycle to cycle, and to make matters worse, investors typically disagree about the prevailing fundamentals, but nonetheless, fundamentals seem to be very important. You have your CFA charter, yet it sounds like you don’t closely follow the fundamentals for individual stocks. Why not?

Q: You mentioned how fundamental trends are what drive stocks higher over time. Granted, as you say, the actual drivers might be different from cycle to cycle, and to make matters worse, investors typically disagree about the prevailing fundamentals, but nonetheless, fundamentals seem to be very important. You have your CFA charter, yet it sounds like you don’t closely follow the fundamentals for individual stocks. Why not?

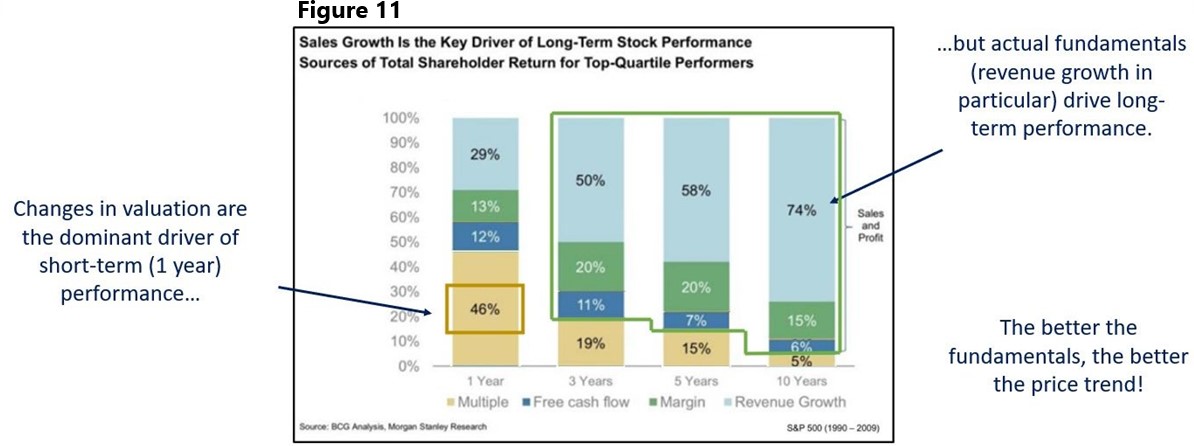

A: First, it is correct to say that fundamentals matter. In fact, if one were to ask me which trends are more important, fundamental or technical, I would say fundamental, hands down. Without strong fundamental trends, there simply are no strong technical trends, period. In fact, a study by Morgan Stanley showed how almost half of what a stock does in the short term (less than a year) is driven by valuation expansion or contraction; but looking out 3 to 10 years, 80-95% of what drives a stock’s price is the company’s actual fundamentals, particularly topline revenue growth. (Figure 11).

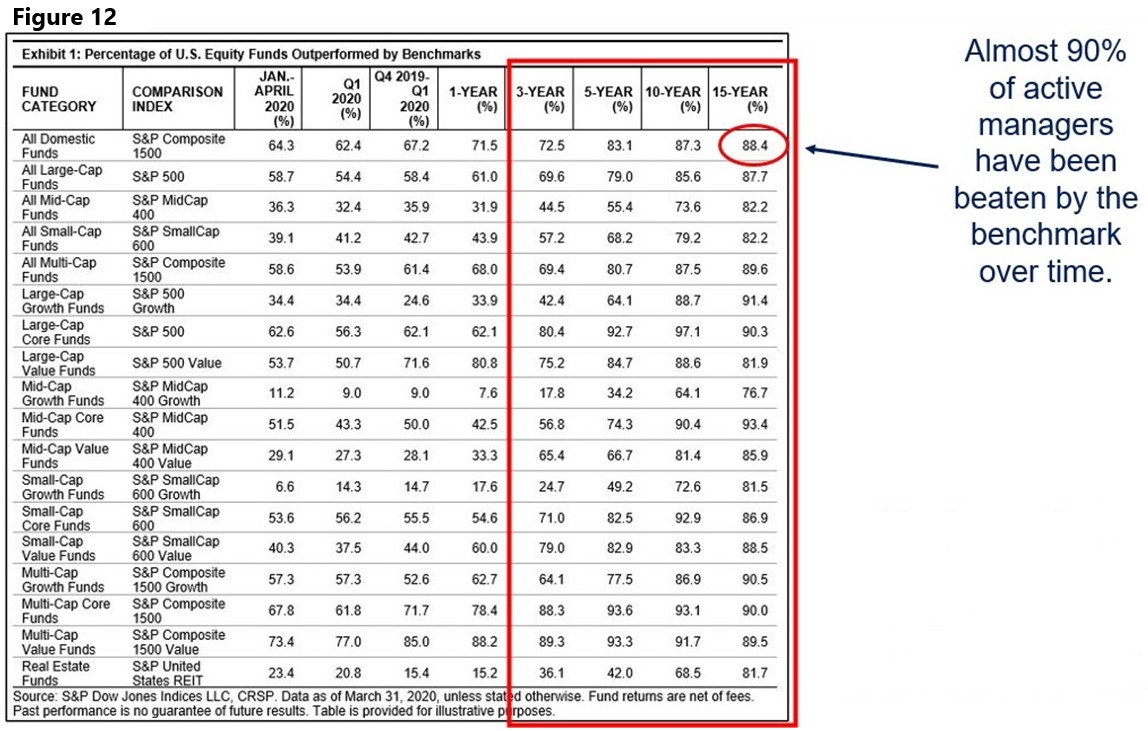

So, clearly, fundamentals are very important. That being said, there is a significant difference between actual fundamental trends and investor opinions about those trends. The data is critical, but opinions about the data are where we get ourselves in trouble. Despite the combined efforts of MBAs, PhDs and Nobel Laureates, almost 90% of active managers with opinions about fundamentals have struggled to beat the market over time. (Figure 12).

So, clearly, fundamentals are very important. That being said, there is a significant difference between actual fundamental trends and investor opinions about those trends. The data is critical, but opinions about the data are where we get ourselves in trouble. Despite the combined efforts of MBAs, PhDs and Nobel Laureates, almost 90% of active managers with opinions about fundamentals have struggled to beat the market over time. (Figure 12).

In the end, it is not that I don’t believe in fundamentals. In fact, there is nobody in the business that believes in fundamentals more than me. Its just that, for reasons that I think are made clear by the long-term performance of active fundamental managers, I don’t value opinions about fundamentals, my own included. The market is the best fundamental analyst on the planet, which is why it is so hard to beat.

So, rather than argue with the market, I have checked my ego at the door, effectively hiring the market to conduct my fundamental analysis for me. I meet with the market every day and intently listen to what it has to say, through the lens of my “MOTR” research process.

Q: Technical analysis has been around for well over 100 years, yet academia, the media and many pure fundamental investors continue to deride those who rely on it to invest. Why is that?

A: In a word, ego. People tend to forget that technical analysis was originally developed well over 100 years ago by private investors in order to protect themselves against the fact that there was no reliable source of fundamental information, and stocks were regularly manipulated for profit, and insider information was not illegal. This was when there was no such thing as the SEC, or any shareholder protections to speak of. So, the only way for the public to gain an edge was to listen to what the market was saying.

This was of course prior to computers, when everything was done by hand, so there are many remnants from that age that academia and the uninitiated media scoff at today, like pattern naming conventions, and the like, but the reality is that academia itself has flooded the world with hundreds of white papers validating many trend following concepts that have their roots in technical analysis literature, dating all the way back to the late 1800s.

This undeniable proof, provided by academia itself, puts them in a tough spot. The fact is that active fundamental managers have failed to keep up with their benchmarks utilizing academic concepts like market efficiency, CAPM, present value of cashflows, etc. The idea that you can improve investment outcomes by leaning on some pretty simple trend following concepts becomes a very large, but self-made pill for academia to swallow.

One of my Chinese students at Brandeis once told me that the reason my class filled up so quickly with students from China was because they couldn’t trust anything that management told them, so they had to learn how to interpret trends. Sound familiar? That’s the United States in the early 1900’s, and the very reason technical analysis was developed in the first place!

So, whether we’re trying to protect ourselves from faulty academic theories, lazy click-bait journalism, the misinformation of company management, the manipulation of other investors, or our very own behavioral biases, technical analysis is as valid and practical today as it has ever been. To paraphrase Don Rumsfeld, “the market has considered everything we think we know, everything we know we don’t know, and most importantly, everything we don’t even know we don’t know.”

This is the power of Benjamin Graham’s proverbial “Weighing Machine”. In the long run, the market figures out what matters, and ignores what doesn’t, all of which manifests in the form of price trends. Our job is to listen to and accept the verdict of the market.

Read Stalking for Fish, and Fishing for Stocks to learn about important trend following investing principles I was reminded of while recently fishing on a remote lake in the beautiful state of Maine.